Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

This article describes how to scale an Internet of Things (IoT) solution by using a scale-out pattern on the Azure IoT Hub platform. The scale-out pattern addresses scaling challenges by adding instances to a deployment instead of increasing instance size. This implementation guidance shows you how to scale an IoT solution that supports millions of devices and considers Azure service and subscription limits. The article outlines low-touch and zero-touch deployment models of the scale-out pattern that you can adopt depending on your needs.

For more information, see the following articles:

- Best practices for large-scale Microsoft Azure IoT device deployments

- IoT Hub

- IoT Hub Device Provisioning Service (DPS)

Note

This document doesn't cover the Azure IoT Operations platform, which scales based on the hosting Kubernetes platform configuration.

Gather requirements

Gather requirements before you implement a new IoT solution. This step helps ensure that the implementation meets your business objectives. Your business objectives and operational environment should drive your requirements. At a minimum, gather the following requirements:

Identify the types of devices that you want to deploy. IoT encompasses a wide range of solutions, from simple microcontroller units (MCUs) to mid-level system-on-chip (SoC) and microprocessor units (MPUs), to full PC-level designs. Device-side software capabilities directly influence the solution design.

Determine the number of devices that you need to deploy. Some basic principles of implementing IoT solutions apply at all scales. Understand the scale to help avoid overengineering a solution. A solution for 1,000 devices has fundamental differences compared to a solution for 1 million devices. A proof-of-concept (PoC) solution for 10,000 devices might not scale appropriately to 10 million devices if you don't consider the target scale at the start of the solution design.

Identify how many devices you need to deploy so that you can choose the right Azure IoT service. The scaling for IoT Hub and IoT Hub DPS differs. By design, a single DPS instance can route to multiple IoT Hub instances. So consider the scale of each service individually with respect to the number of devices. But limits don't exist in isolation. If one service presents a limit concern, other services likely do too. Treat service limits as distinct but related quotas.

Document the anticipated device locations. Include physical location, power availability, and internet connectivity. A solution that you deploy in a single geography, such as only in North America, is designed differently compared to a global solution. Likewise, an industrial IoT solution deployed in factories that have full-time power differs from a fleet management solution deployed in motor vehicles that have variable power and location. The communication protocol and available bandwidth, whether to a gateway or directly to a cloud service, affect design scalability at each layer. Also consider connectivity availability. Determine whether devices remain connected to Azure or run in a disconnected mode for extended periods.

Investigate data locality requirements. Legal, compliance, or customer requirements might restrict where you can store data (such as telemetry) or metadata (such as device information) for the solution. These restrictions significantly influence the solution's geographical design.

Determine data exchange requirements. A solution that sends basic telemetry such as current temperature once per hour differs from a solution that uploads 1-MB sample files once every 10 minutes. A one-way, device-to-cloud (D2C) solution differs from a bidirectional D2C and cloud-to-device (C2D) solution. Also, product scalability limitations treat message size and message quantity as different dimensions.

Document expected high availability and disaster recovery requirements. Like any production solution, full IoT solution designs include availability, or uptime, requirements. The design needs to cover both planned maintenance scenarios and unplanned downtime, including user errors, environmental factors, and solution bugs. The design also needs to have a documented recovery point objective (RPO) and recovery time objective (RTO) if a disaster occurs, such as a permanent region loss or malicious actors. This article focuses on device scale, so it includes only limited information about high availability and disaster recovery concerns.

Decide on a customer tenancy model if appropriate. In a multitenant software development company solution, where the solution developer creates a solution for external customers, the design must define how to segregate and manage customer data. For more information, see Tenancy models and the related IoT-specific guidance.

Understand Azure IoT concepts

When you create a solution, choose the appropriate Azure IoT components and other supporting Azure services. The architecture of your solution requires significant effort. Properly using the IoT Hub and IoT Hub DPS services can help you scale your solutions to millions of devices.

IoT Hub

IoT Hub is a managed service hosted in the cloud that acts as a central message hub for communication between an IoT application and its attached devices. You can use IoT Hub alone or with IoT Hub DPS.

IoT Hub scales based on the desired functionality and the number of messages or volume of data per day. Use the following three inputs to determine how to scale an instance:

The free, basic, and standard tiers determine the available capabilities. A production instance doesn't use the free tier because it's limited in scale and intended for introduction development scenarios only. Most solutions use the standard tier to get the full capabilities of IoT Hub.

The size determines the message and data throughput base unit for D2C messages for IoT Hub. The maximum size for an instance of IoT Hub is size 3, which supports 300 million messages per day and 1,114.4 GB of data per day, per unit.

The unit count determines the multiplier for the scale on size. For example, three units support three times the scale of one unit. The limit on size 1 or 2 hub instances is 200 units, and the limit on size 3 hub instances is 10 units.

In addition to the daily limits based on the size and unit count and the general functionality limits based on tier, IoT Hub enforces per-second limits on throughput. Each IoT Hub instance also supports up to 1 million devices as a hard limit. Your data exchange requirements help define the appropriate configuration. For more information, see Other limits.

Your solution requirements drive the necessary size and number of IoT Hub instances as a starting point. If you use IoT Hub DPS, Azure helps you distribute your workloads across multiple IoT Hub instances.

IoT Hub DPS

IoT Hub DPS is a helper service for IoT Hub that enables zero-touch, just-in-time provisioning to the right IoT hub without requiring human intervention. Each Azure subscription supports a maximum of 10 DPS instances. Each service instance supports a maximum of 1 million registrations. Address service limits in your workload design limit to avoid problems in the future.

DPS instances reside in specific geographic regions but have a global public endpoint by default. Specific instances are accessed through an ID scope. Because instances are in specific regions and each instance has its own ID scope, you should be able to configure the ID scope for your devices.

Understand shared resiliency concepts

You must consider shared resiliency concepts, such as transient fault handling, device location impact, and, for software companies, software as a service (SaaS) data resiliency.

Understand transient fault handling. Any production distributed solution, whether it's on-premises or in the cloud, must be able to recover from transient or temporary faults. Transient faults might occur more frequently in a cloud solution because of the following factors:

- Reliance on an external provider

- Reliance on the network connectivity between the device and cloud services

- Implementation limits of cloud services

Transient fault handling requires you to have a retry capability built into your device code. Several retry strategies exist, including exponential backoff with randomization, also known as exponential backoff with jitter. For more information, see Transient fault handling.

Different factors can affect the network connectivity of a device:

The power source of a device: Battery-powered devices or devices powered by transient sources, such as solar or wind, might have less network connectivity than full-time line-powered devices.

The deployment location of a device: Devices in urban factory settings likely have better network connectivity than devices in isolated field environments.

The location stability of a device: Mobile devices likely have less network connectivity than fixed-location devices.

These concerns also affect the timing of device availability and connectivity. For example, line-powered devices in dense, urban environments, such as smart speakers, might disconnect and reconnect in large groups. Consider the following scenarios:

A blackout might cause 1 million devices to go offline at the same time and come back online simultaneously because of power grid loss and reconnection. This scenario applies in both consumer scenarios, such as smart speakers, and business and industrial IoT scenarios, such as connected, line-powered thermostats reporting to a real-estate management company.

During a short-timeframe, large-scale onboarding event, such as Black Friday or Christmas, many consumers power on devices for the first time in a relatively short period of time.

Many devices receive scheduled updates in a short time window, and all of them reboot with the new update at approximately the same time.

These many devices booting at once scenarios can trigger cloud service throttling, even with near-constant network connectivity.

Beyond network and quota problems, you should also consider Azure service outages. These outages might affect individual services or entire regions. Some services, such as IoT Hub, support geo-redundancy. Other services, such as IoT Hub DPS, store their data in a single region. You can link one IoT hub to multiple DPS instances, which helps mitigate regional risks.

If regional redundancy is a concern, use the Geode pattern. This pattern hosts independent, grouped resources across different geographies. Similarly, a deployment stamp, also known as a scale stamp, applies this pattern to operate multiple workloads or tenants. For more information, see Deployment Stamps pattern.

Understand device location impact. Most Azure services are regional, even DPS with global endpoints. Exceptions include Azure Traffic Manager and Microsoft Entra ID. Your decisions about device location, data location, and metadata location (such as Azure resource groups) play a critical role in your design.

Device location: Device location requirements affect your regional selection because they affect transactional latency.

Data location: Data location is tied to device location, which is subject to compliance concerns. For example, a solution that stores data for a state in the United States might require data storage in the US geography. Data locality requirements might also drive this need.

Metadata location: Although device location doesn't usually affect metadata location because devices interact with solution data and not solution metadata, compliance and cost concerns affect metadata location. In many cases, convenience dictates that the metadata location is the same as the data location for regional services.

The Azure Cloud Adoption Framework includes guidance about regional selection.

Understand software company SaaS concerns. Software companies that offer SaaS solutions should meet customers' expectations for availability and resiliency. Software companies must architect Azure services to be highly available and consider the cost of resiliency and redundancy when billing the customer.

Segregate the cost of goods sold based on customer data segregation for each software customer. This distinction is important when the user isn't the same as the customer. For example, for a smart TV platform, the platform vendor's customer might be the television vendor, but the user is the purchaser of the television. This segregation, driven by the customer tenancy model from the requirements, requires separate DPS and IoT Hub instances. The provisioning service must also have a unique customer identity, which you can define through a unique endpoint or device authentication process. For more information, see IoT multitenant guidance.

Scale out components and their supporting services

When you scale IoT solutions, evaluate each service and how they interrelate. You can scale your IoT solution across multiple DPS instances or by using IoT Hub.

Scale out across multiple DPS instances

Because of DPS service limits, you often need to expand to multiple DPS instances. You can approach device provisioning across multiple DPS instances through either zero-touch provisioning or low-touch provisioning.

The following approaches apply the previously described stamp concept for resiliency and scaling out. This concept includes deploying Azure App Service in multiple regions and using a tool such as Traffic Manager or a global load balancer. For simplicity, the following diagrams don't show these components.

Approach 1: Zero-touch provisioning with multiple DPS instances

For zero-touch or automated provisioning, a proven strategy includes having the device request a DPS ID scope from a web API. The API understands and balances devices across the horizontally scaled-out DPS instances. This action makes the web app a critical part of the provisioning process, so it must be scalable and highly available. This design has three primary variations.

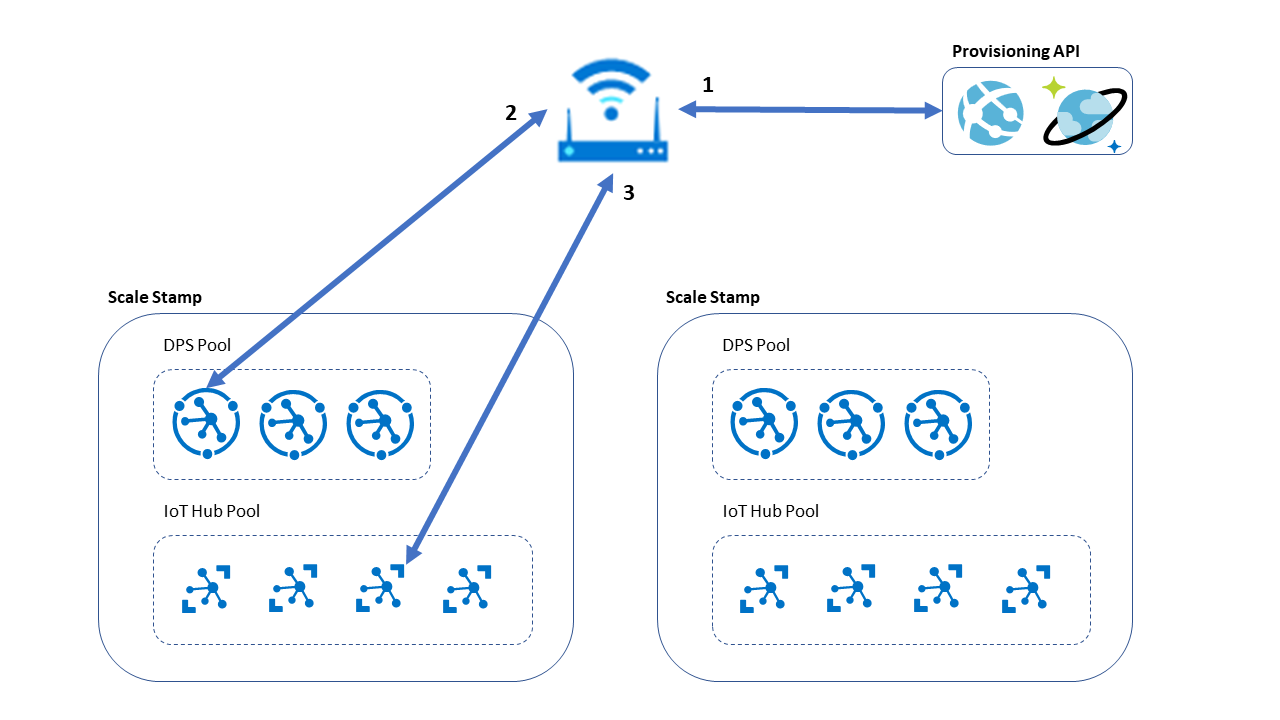

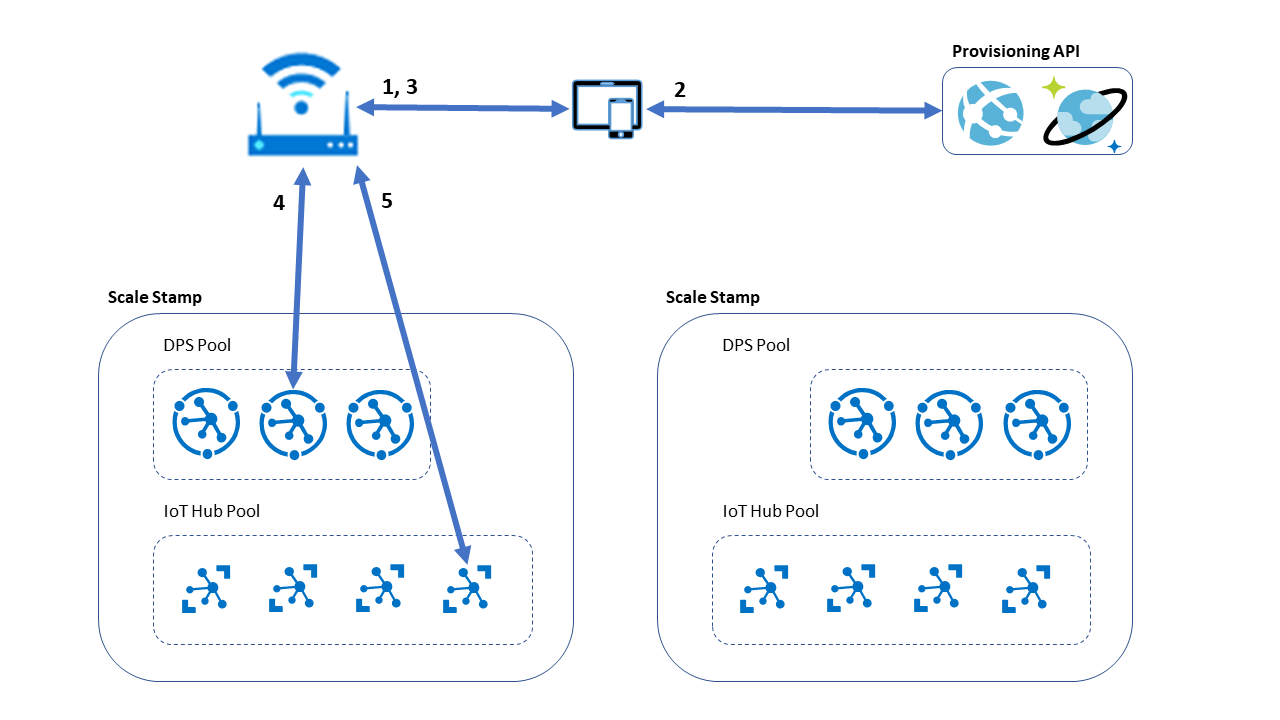

The following diagram shows the first option that uses a custom provisioning API that manages how to map the device to the appropriate DPS pool. Each DPS instance then maps the device to the appropriate IoT Hub by using standard DPS load balancing mechanisms.

The device makes a request to a provisioning API hosted in App Service to request a DPS ID scope. The provisioning API checks with its persistent database to determine the best instance for the device, based on existing device inventory, and returns the DPS ID scope.

In this example, the database is an Azure Cosmos DB instance that has multi-primary write enabled for cross-region high availability. This database stores each device's assigned DPS. It supports tracking DPS instance usage for all appropriate metrics, such as provision requests per minute and total provisioned devices. This database also enables reprovisioning with the same DPS ID scope when needed. Authenticate the provisioning API to prevent inappropriate provisioning requests.

The device makes a request against DPS by using the assigned ID scope. DPS responds with IoT hub assignment details.

The device stores the ID scope and IoT hub connection information in persistent storage, ideally in a secured storage location because the ID scope is part of the authentication against the DPS instance. The device then uses this IoT hub connection information for further requests into the system.

This design requires the device software to include the DPS SDK and manage the DPS enrollment process, which is the typical design for an Azure IoT device. But in a microcontroller environment, where device software size is a critical component of the design, it might not be acceptable and might require an alternative design.

Approach 2: Zero-touch provisioning with a provisioning API

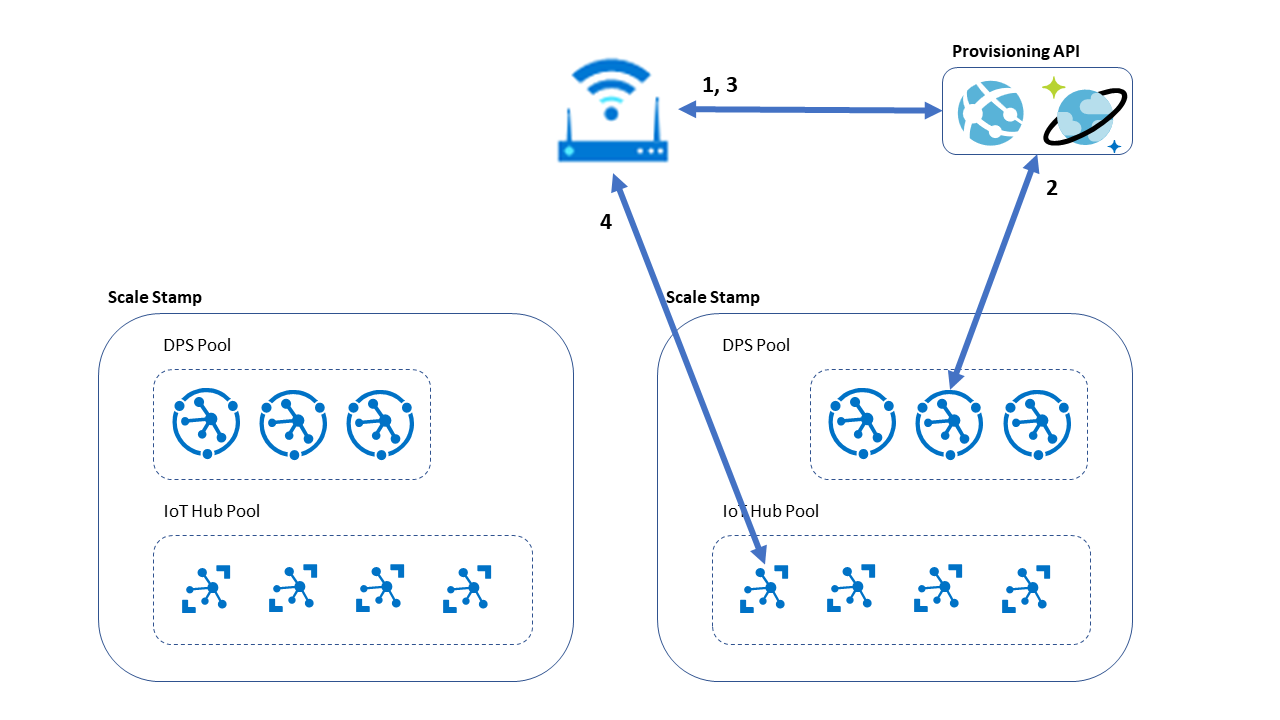

The second design moves the DPS call to the provisioning API. In this model, the device authentication against DPS is contained in the provisioning API, as is most of the retry logic. This process allows more advanced queuing scenarios and potentially simpler provisioning code in the device itself. It also allows for caching the assigned IoT hub to facilitate faster C2D messaging. The messages are sent without needing to interrogate DPS for the assigned hub information.

The device makes a request to a provisioning API hosted in an instance of App Service. The provisioning API checks with its persistent database to determine the best instance for the device based on existing device inventory, and then it determines the DPS ID scope.

In this example, the database is an Azure Cosmos DB instance that has multi-primary write enabled for cross-region high availability. This database stores each device's assigned DPS. It supports tracking DPS instance usage for all appropriate metrics. The database also enables reprovisioning by using the same DPS ID scope when needed.

Authenticate the provisioning API to prevent inappropriate provisioning requests. You can likely use the same authentication that the provisioning service uses against DPS, such as a private key for an issued certificate. But other options exist. For example, FastTrack for Azure might work with a customer that uses hardware unique identifiers as part of their service authentication process. The device manufacturing partner regularly supplies a list of unique identifiers to the device vendor to load into a database, which references the service behind the custom provisioning API.

The provisioning API performs the DPS provisioning process by using the assigned ID scope, effectively acting as a DPS proxy.

The API forwards the DPS results to the device.

The device stores the IoT hub connection information in persistent storage, ideally in a secured storage location because the ID scope is part of the authentication against the DPS instance. The device uses this IoT hub connection information for later requests into the system.

This design avoids the need to reference the DPS SDK or the DPS service. It also avoids the need for storing or maintaining a DPS scope on the device. This model supports transfer-of-ownership scenarios because the provisioning service can direct to the appropriate final customer DPS instance. However, this approach causes the provisioning API to duplicate some DPS functionality, which might not suit all scenarios.

Approach 3: Zero-touch provisioning with transfer of ownership

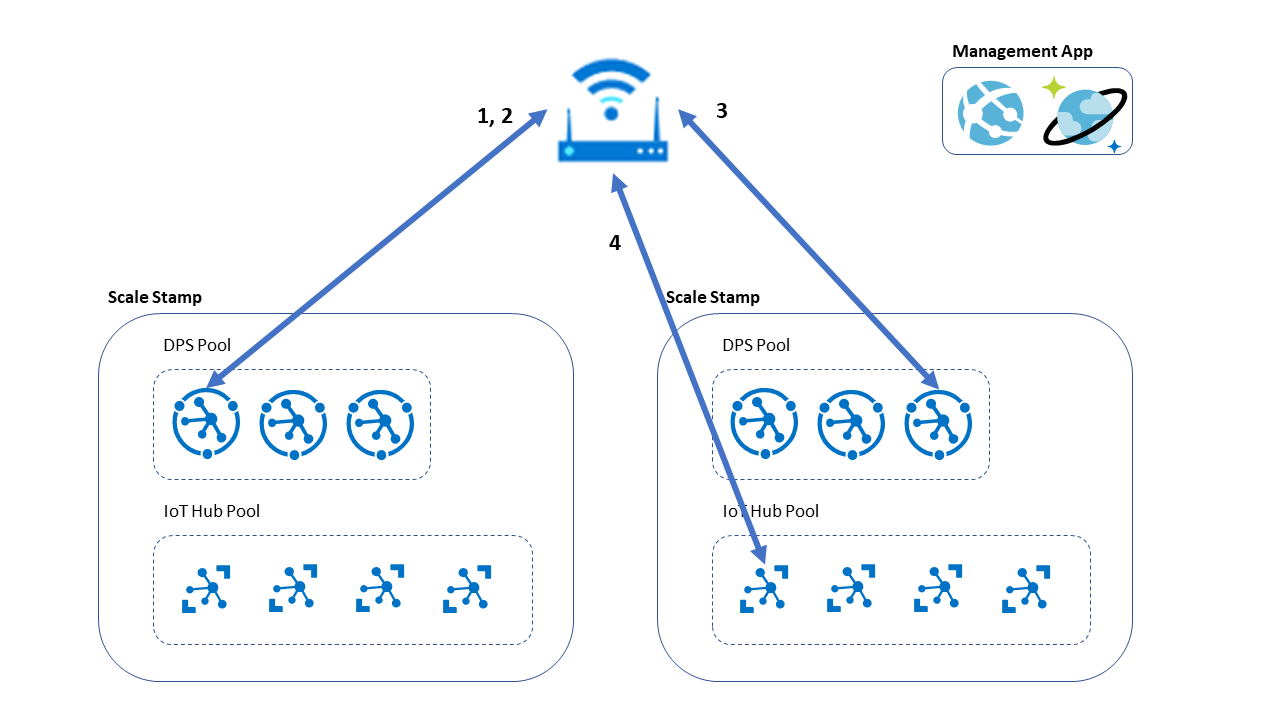

A third zero-touch provisioning design uses a factory-configured DPS instance as a starting point and redirects devices to other DPS instances as necessary. This design allows for provisioning without a custom provisioning API, but it requires a management application to track DPS instances and supply redirection as necessary.

The management application requirements include tracking which DPS should be the active DPS for each specific device. You can use this approach for transfer-of-ownership scenarios, where the device vendor transfers ownership of the device from the vendor to the end device customer.

The device connects to the factory-configured DPS instance and requests an initial provisioning process.

The device receives an initial configuration, including the desired target DPS instance.

The device connects to the desired target DPS instance and requests provisioning.

The device stores the IoT hub connection information in persistent storage, ideally in a secured storage location because the ID scope is part of the authentication against the DPS instance. The device uses this IoT hub connection information for further requests into the system.

Approach 4: Low-touch provisioning with multiple DPS instances

In some cases, such as in consumer-facing scenarios or field deployment team devices, a common choice is to offer low-touch, or user-assisted, provisioning. Examples of low-touch provisioning include a mobile application on an installer's phone or a web-based application on a device gateway. This approach performs the same operations as the zero-touch provisioning process, but the provisioning application transfers the details to the device.

The administrator launches a device configuration app, which connects to the device.

The configuration app connects to a provisioning API hosted in an instance of App Service to request a DPS ID scope. The provisioning API checks its persistent database to determine the best instance for the device, based on existing device inventory, and returns the DPS ID scope.

In this example, the database is an Azure Cosmos DB instance that has multi-primary write enabled for cross-region high availability. This database stores each device's assigned DPS. It supports tracking usage of the DPS instances for all appropriate metrics. This database also enables reprovisioning by using the same DPS ID scope when needed. Authenticate the provisioning API to prevent inappropriate provisioning requests from being serviced.

The app returns the provisioning ID scope to the device.

The device makes a request against DPS with the assigned ID scope. DPS returns IoT hub assignment details to the device.

The device persists the ID scope and IoT hub connection information to persistent storage, ideally in a secured storage location because the ID scope is part of the authentication against the DPS instance. The device uses this IoT hub connection information for further requests into the system.

This article doesn't cover other variations. For example, you can configure this approach by moving the DPS call to the provisioning API, as shown earlier in the zero-touch provisioning with a provisioning API. The goal is to make sure that each tier is scalable, configurable, and readily deployable.

General DPS provisioning guidance

Apply the following recommendations to your DPS deployment:

Don't provision on every boot. The DPS documentation recommends that you don't provision on every boot. For small use cases, it might seem reasonable to provision on every boot because that's the shortest path to deployment. However, when you scale up to millions of devices, DPS can become a bottleneck because of its hard limit of 1,000 registrations per minute, per service instance. Even device registration status lookups can become a bottleneck because they have a limit of 5 to 10 polling operations per second. Provisioning results typically map statically to an IoT hub. So you should only initiate provisioning when necessary, unless your requirements include automated reprovisioning requests. If you anticipate more traffic, scale out to multiple DPS instances to support your scenario.

Use a staggered provisioning schedule. To reduce time-based limitations, use a staggered provisioning schedule. For initial provisioning, you can apply a random delay of a few seconds or extend the delay to minutes, depending on the deployment requirements.

Always query status before requesting provisioning. As a best practice, devices should always query their status before requesting provisioning by using the Device Registration Status Lookup API. This call doesn't count as a billed item, and the limit is independent of the registration limit. The query operation is relatively quick compared to a provision request, which means that the device can validate its status and move on to the normal device workload more quickly. For the appropriate device registration logic, see Large-scale deployment.

Follow provisioning API considerations. Several of the designs in this article include a provisioning API. The provisioning API needs a backing metadata store, such as Azure Cosmos DB. At these scale levels, you should implement a globally available and resilient design pattern. The built-in multi-primary, geo-redundant capabilities and latency guarantees in Azure Cosmos DB make it an excellent choice for this scenario. This API has the following key responsibilities:

Serve the DPS ID scope. This interface might use a GET request. Physical devices or management applications connect to this interface.

Support the device life cycle. A device might require reprovisioning, or unexpected events can happen. At a minimum, maintain the device ID and assigned DPS for a device. This information enables deprovisioning from the assigned DPS and reprovisioning on another. Or if a device's life cycle is over, you can completely remove it from the system.

Load balance systems. The system uses the same metadata regarding device ID and DPS, so it can understand the current load on each subsystem and apply that information to better balance devices across the horizontally scaled-out components.

Uphold system security. The provisioning API should authenticate each request. The recommended best practice is to use a unique X.509 certificate for each device. This certificate can authenticate the device against both the provisioning API and the DPS instance, if the architecture supports it. Other methods, such as fleet certificates and tokens, are available but provide less security. Your specific implementation and its security implications depend on whether you choose a zero-touch or low-touch option.

Scale out IoT Hub

Compared to scaling out DPS, scaling out IoT Hub is relatively straightforward. One of the benefits of DPS is its ability to link to many IoT Hub instances. When you follow the recommended practice of using DPS in Azure IoT solutions, scaling out IoT Hub involves the following steps:

Create a new instance of the IoT Hub service.

Configure the new instance with appropriate routing rules and other details.

Link the new instance to the appropriate DPS instances.

If necessary, reconfigure the DPS allocation policy or your custom allocation policy.

Design device software

Scalable device design requires following best practices and device-side considerations. Some of these practices come from anti-patterns encountered in the field. This section describes key concepts for a successfully scaled deployment.

Estimate workloads across different parts of the device life cycle and scenarios within the life cycle. Device registration workloads can vary greatly between development phases, such as pilot, development, production, decommissioning, and end of life. In some cases, they can also vary based on external factors such as the previously mentioned blackout scenario. Design for the worst-case workload to help ensure success at scale.

Support reprovisioning on demand. You can provide this feature through a device command and an administrative user request. For more information, see Reprovision devices. This option facilitates transfer-of-ownership scenarios and factory-default scenarios.

Avoid unnecessary reprovisioning. Active, working devices rarely require reprovisioning because provisioning information remains relatively static. Don't reprovision without a good reason.

Check provisioning status if you must reprovision often, for example at every device boot. If you're unsure about the device provisioning status, query the provisioning status first. The query operation is handled against a different quota than a provisioning operation and is faster. This query allows the device to validate the provisioning status before proceeding. This approach is especially useful when a device doesn't have available persistent storage to store the provisioning results.

Ensure a good retry logic strategy. The device must have appropriate retry algorithms built into the device code for both initial provisioning and later reprovisioning. Use techniques such as exponential backoff with randomization. Initial provisioning, by definition, might need to be more aggressive in the retry process than reprovisioning, depending on the use case. When throttled, DPS returns an HTTP 429 Too Many Requests error code, like most Azure services. For more information, see Retry and Anti-patterns to avoid. The DPS documentation also explains how to interpret service retry recommendations and calculate jitter. The device location stability and connectivity access also influence the appropriate retry strategy. For example, if a device detects that it's offline for periods of time, it should avoid retrying online operations.

Support over-the-air (OTA) updates. Two simple update models include using device twin properties with automatic device management and using simple device commands. For more sophisticated update scenarios and reporting, see Azure Device Update. OTA updates allow you to fix defects in device code and reconfigure services, such as DPS ID scope, if necessary.

Architect for certificate changes at all layers and certificate uses. This recommendation aligns with the OTA update best practices. You must consider certificate rotation. The IoT Hub DPS documentation addresses this scenario from a device identity certificate viewpoint. In a device solution, other certificates are used for access to services like IoT Hub, App Service, and Azure Storage accounts. Azure sometimes changes certificate authority configurations, so you must anticipate changes at all layers. Also, use certificate pinning with caution, especially when certificates are outside the device manufacturer's control.

Consider a reasonable default state. To resolve initial provisioning failures, have a reasonable disconnected or unprovisioned configuration, depending on the circumstances. If the device has a heavy interaction component as part of initial provisioning, the provision process can occur in the background while the user performs other provisioning tasks. Always pair this approach with an appropriate retry pattern and the Circuit Breaker pattern.

Include endpoint configuration capabilities where appropriate. Allow configuration of the DPS ID scope, the DPS endpoint, or the custom provisioning service endpoint. Although the DPS endpoint rarely changes, enabling this flexibility supports scenarios such as automated validation of the device provisioning process through integration testing without direct Azure access or future provisioning models that use a proxy service.

Use the Azure IoT SDKs for provisioning. Whether the DPS calls are on the device itself or in a custom provisioning API, use the Azure IoT SDKs to benefit from built-in best practices and simplify support. The SDKs are published open source, so you can review how they work and suggest changes. Your choice of SDK depends on the device hardware and available runtimes on the device.

Deploy devices

Device deployment is a key part of the device life cycle, but it's outside the scope of this article because it's dependent on the use case. The previously referenced discussion points about transfer of ownership might apply to the deployment and patterns that involve a provisioning application, such as a mobile application. But you must select the deployment approach based on the IoT device type in use.

Monitor devices

An important part of your overall deployment is to monitor the solution from start to finish to make sure that the system performs appropriately. This article explicitly focuses on architecture and design and not the operational aspects of the solution, so monitoring isn't included. However, at a high level, monitoring tools are built into Azure through Azure Monitor to ensure that the solution doesn't reach limits. For more information, see the following articles:

You can use these tools individually or as part of a more sophisticated Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) solution like Microsoft Sentinel.

Use the following monitoring patterns to monitor DPS usage over time:

Create an application that queries each enrollment group on a DPS instance, retrieves the total devices registered to that group, and then aggregates the numbers from across various enrollment groups. This method provides an exact count of devices currently registered via DPS and helps monitor the state of the service.

Monitor device registrations over a specific period. For instance, you can monitor registration rates for a DPS instance over the previous five days. This approach provides only an approximate figure and is limited to a set time period.

Conclusion

Scaling up an IoT solution to support millions, or even hundreds of millions, of devices requires careful planning. You must consider many factors and various ways to solve the problems that arise at those scales. This article summarizes the key concerns and provides approaches about how to address those concerns in a successful deployment.

Contributors

Microsoft maintains this article. The following contributors wrote this article.

Principal author:

- Michael C. Bazarewsky | Senior Customer Engineer, Microsoft Azure CXP

Other contributors:

- David Crook | Principal Customer Engineer, Microsoft Azure CXP

- Alberto Gorni | Former Senior Customer Engineer, Microsoft Azure CXP

To see nonpublic LinkedIn profiles, sign in to LinkedIn.